In Episode 38, you can listen to Lafcadio Hearn’s whimsical take on the cicada (semi) while enjoying some real time cicada singing in the background.

Excerpt from Shadowings (Lafcadio Hearn), Semi (Cicada) available on Project Gutenberg.

Thank you for listening!

Terrie

I

A celebrated Chinese scholar, known in Japanese literature as Riku-Un, wrote the following quaint account of the Five Virtues of the Cicada:—

“I.—The Cicada has upon its head certain figures or signs. These represent its [written] characters, style, literature.

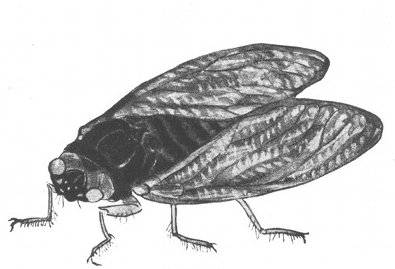

The curious markings on the head of one variety of Japanese sémi are believed to be characters which are names of souls.

“II.—It eats nothing belonging to earth, and drinks only dew. This proves its cleanliness, purity, propriety.

“III.—It always appears at a certain fixed time. This proves its fidelity, sincerity, truthfulness.

“IV.—It will not accept wheat or rice. This proves its probity, uprightness, honesty.

“V.—It does not make for itself any nest to live in. This proves its frugality, thrift, economy.”

We might compare this with the beautiful address of Anacreon to the cicada, written twenty-four hundred years ago: on more than one point the Greek poet and the Chinese sage are in perfect accord:—

“We deem thee happy, O Cicada, because, having drunk, like a king, only a little dew, thou dost chirrup on the tops of trees. For all things whatsoever that thou seest in the fields are thine, and whatsoever the seasons bring forth. Yet art thou the friend of the tillers of the land,—from no one harmfully taking aught. By mortals thou art held in honor as the pleasant harbinger of summer; and the Muses love thee. Phœbus himself loves thee, and has given thee a shrill song. And old age does not consume thee. O thou gifted one,—earth-born, song-loving, free from pain, having flesh without blood,—thou art nearly equal to the Gods! “

It is especially in their poems upon the cicada that we find the old Greeks confessing their love of insect-melody: witness the lines in the Anthology about the tettix caught in a spider’s snare, and “making lament in the thin fetters” until freed by the poet;—and the verses by Leonidas of Tarentum picturing the “unpaid minstrel to wayfaring men” as “sitting upon lofty trees, warmed with the great heat of summer, sipping the dew that is like woman’s milk;”—and the dainty fragment of Meleager, beginning: “Thou vocal tettix, drunk with drops of dew, sitting with thy serrated limbs upon the tops of petals, thou givest out the melody of the lyre from thy dusky skin.” … Or take the charming address of Evenus to a nightingale:—

“Thou Attic maiden, honey-fed, hast chirping seized a chirping cicada, and bearest it to thy unfledged young,—thou, a twitterer, the twitterer,—thou, the winged, the well-winged,—thou, a stranger, the stranger,—thou, a summer-child, the summer-child! Wilt thou not quickly cast it from thee? For it is not right, it is not just, that those engaged in song should perish by the mouths of those engaged in song.”

On the other hand, we find Japanese poets much more inclined to praise the voices of night-crickets than those of sémi. There are countless poems about sémi, but very few which commend their singing. Of course the sémi are very different from the cicadæ known to the Greeks. Some varieties are truly musical; but the majority are astonishingly noisy,—so noisy that their stridulation is considered one of the great afflictions of summer. Therefore it were vain to seek among the myriads of Japanese verses on sémi for anything comparable to the lines of Evenus above quoted; indeed, the only Japanese poem that I could find on the subject of a cicada caught by a bird, was the following:—

Ana kanashi!

Tobi ni toraruru

Sémi no koë.

—Ransetsu.

Ah! how piteous the cry of the sémi seized by the kite!

Or “caught by a boy” the poet might equally well have observed,—this being a much more frequent cause of the pitiful cry. The lament of Nicias for the tettix would serve as the elegy of many a sémi:—

“No more shall I delight myself by sending out a sound from my quick-moving wings, because I have fallen into the savage hand of a boy, who seized me unexpectedly, as I was sitting under the green leaves.”

Here I may remark that Japanese children usually capture sémi by means of a long slender bamboo tipped with bird-lime (mochi). The sound made by some kinds of sémi when caught is really pitiful,—quite as pitiful as the twitter of a terrified bird. One finds it difficult to persuade oneself that the noise is not a voice of anguish, in the human sense of the word “voice,” but the production of a specialized exterior membrane. Recently, on hearing a captured sémi thus scream, I became convinced in quite a new way that the stridulatory apparatus of certain insects must not be thought of as a kind of musical instrument, but as an organ of speech, and that its utterances are as intimately associated with simple forms of emotion, as are the notes of a bird,—the extraordinary difference being that the insect has its vocal chords outside. But the insect-world is altogether a world of goblins and fairies: creatures with organs of which we cannot discover the use, and senses of which we cannot imagine the nature;—creatures with myriads of eyes, or with eyes in their backs, or with eyes moving about at the ends of trunks and horns;—creatures with ears in their legs and bellies, or with brains in their waists! If some of them happen to have voices outside of their bodies instead of inside, the fact ought not to surprise anybody.

I have not yet succeeded in finding any Japanese verses alluding to the stridulatory apparatus of sémi,—though I think it probable that such verses exist. Certainly the Japanese have been for centuries familiar with the peculiarities of their own singing insects. But I should not now presume to say that their poets are incorrect in speaking of the “voices” of crickets and of cicadæ. The old Greek poets who actually describe insects as producing music with their wings and feet, nevertheless speak of the “voices,” the “songs,” and the “chirruping” of such creatures,—just as the Japanese poets do.

II

BEFORE speaking further of the poetical literature of sémi, I must attempt a few remarks about the sémi themselves. But the reader need not expect anything entomological. Excepting, perhaps, the butterflies, the insects of Japan are still little known to men of science; and all that I can say about sémi has been learned from inquiry, from personal observation, and from old Japanese books of an interesting but totally unscientific kind. Not only do the authors contradict each other as to the names and characteristics of the best-known sémi; they attach the word sémi to names of insects which are not cicadæ.

The following enumeration of sémi is certainly incomplete; but I believe that it includes the better-known varieties and the best melodists. I must ask the reader, however, to bear in mind that the time of the appearance of certain sémi [Pg 79]differs in different parts of Japan; that the same kind of sémi may be called by different names in different provinces; and that these notes have been written in Tōkyō.

I.—Haru-Zémi.

Various small sémi appear in the spring. But the first of the big sémi to make itself heard is the haru-zémi (“spring-sémi”), also called uma-zémi (“horse-sémi”), kuma-zémi (“bear-sémi”), and other names. It makes a shrill wheezing sound,—ji-i-i-i-i-iiiiiiii,—beginning low, and gradually rising to a pitch of painful intensity. No other cicada is so noisy as the haru-zémi; but the life of the creature appears to end with the season. Probably this is the sémi referred to in an old Japanese poem:—

Hatsu-sémi ya!

“Koré wa atsui” to

Iu hi yori.

—Taimu.

The day after the first day on which we exclaim, “Oh, how hot it is!” the first sémi begins to cry.

II.—”Shinné-shinné.”

The shinné-shinné—also called yama-zémi, or “mountain-sémi”; kuma-zémi, or “bear-sémi”; and ō-sémi, or “great sémi”—begins to sing as early as May. It is a very large insect. The upper part of the body is almost black, and the belly a silvery-white; the head has curious red markings. The name shinné-shinné is derived from the note of the creature, which resembles a quick continual repetition of the syllables shinné. About Kyōto this sémi is common: it is rarely heard in Tōkyō.

[My first opportunity to examine an ō-sémi was in Shidzuoka. Its utterance is much more complex than the Japanese onomatope implies; I should liken it to the noise of a sewing-machine in full operation. There is a double sound: you hear not only the succession of sharp metallic clickings, but also, below these, a slower series of dull clanking tones. The stridulatory organs are light green, looking almost like a pair of tiny green leaves attached to the thorax.]

III.—Aburazémi.

The aburazémi, or “oil-sémi,” makes its appearance early in the summer. I am told that it owes its name to the fact that its shrilling resembles the sound of oil or grease frying in a pan.

Some writers say that the shrilling resembles the sound of the syllables gacharin-gacharin; but others compare it to the noise of water boiling. The aburazémi begins to chant about sunrise; then a great soft hissing seems to ascend from all the trees. At such an hour, when the foliage of woods and gardens still sparkles with dew, might have been composed the following verse,—the only one in my collection relating to the aburazémi:—

Ano koë dé

Tsuyu ga inochi ka?—

Aburazémi!

Speaking with that voice, has the dew taken life?—Only the aburazémi!

IV.—Mugi-kari-Zémi.

The mugi-kari-zémi, or “barley-harvest sémi,” also called goshiki-zémi, or “five-colored sémi,” appears early in the summer. It makes two distinct sounds in different keys, resembling the syllables shi-in, shin—chi-i, chi-i.

V.—Higurashi, or “Kana-kana.”

This insect, whose name signifies “day-darkening,” is the most remarkable of all the Japanese cicadæ. It is not the finest singer among them; but even as a melodist it ranks second only to the tsuku-tsuku-bōshi. It is the special minstrel of twilight, singing only at dawn and sunset; whereas most of the other sémi make their music only in the full blaze of day, pausing even when rain-clouds obscure the sun. In Tōkyō the higurashi usually appears about the end of June, or the beginning of July. Its wonderful cry,—kana-kana-kana-kana-kana,—beginning always in a very high clear key, and slowly descending, is almost exactly like the sound of a good hand-bell, very quickly rung. It is not a clashing sound, as of violent ringing; it is quick, steady, and of surprising sonority. I believe that a single higurashi can be plainly heard a quarter of a mile away; yet, as the old Japanese poet Yayū observed, “no matter how many higurashi be singing together, we never find them noisy.” Though powerful and penetrating as a resonance of metal, the higurashi’s call is musical even to the degree of sweetness; and there is a peculiar melancholy in it that accords with the hour of gloaming. But the most astonishing fact in regard to the cry of the higurashi is the individual quality characterizing the note of each insect. No two higurashi sing precisely in the same tone. If you hear a dozen of them singing at once, you will find that the timbre of each voice is recognizably different from every other. Certain notes ring like silver, others vibrate like bronze; and, besides varieties of timbre suggesting bells of various weight and composition, there are even differences in tone, that suggest different forms of bell.

I have already said that the name higurashi means “day-darkening,”—in the sense of twilight, gloaming, dusk; and there are many Japanese verses containing plays on the word,—the poets affecting to believe, as in the following example, that the crying of the insect hastens the coming of darkness:—

Higurashi ya!

Sutétéoitémo

Kururu hi wo.

O Higurashi!—even if you let it alone, day darkens fast enough!

This, intended to express a melancholy mood, may seem to the Western reader far-fetched. But another little poem—referring to the effect of the sound upon the conscience of an idler—will be appreciated by any one accustomed to hear the higurashi. I may observe, in this connection, that the first clear evening cry of the insect is quite as startling as the sudden ringing of a bell:—

Higurashi ya!

Kyō no kétai wo

Omou-toki.

—Rikei.

Already, O Higurashi, your call announces the evening!

Alas, for the passing day, with its duties left undone!

VI.—”Minmin”-Zémi.

The minmin-zémi begins to sing in the Period of Greatest Heat. It is called “min-min” because its note is thought to resemble the syllable “min” repeated over and over again,—slowly at first, and very loudly; then more and more quickly and softly, till the utterance dies away in a sort of buzz: “min—min—min-min-min-minminmin-dzzzzzzz.” The sound is plaintive, and not unpleasing. It is often compared to the sound of the voice of a priest chanting the sûtras.

VII.—Tsuku-tsuku-bōshi.

On the day immediately following the Festival of the Dead, by the old Japanese calendar (which is incomparably more exact than our Western calendar in regard to nature-changes and manifestations), begins to sing the tsuku-tsuku-bōshi. This creature may be said to sing like a bird. It is also called kutsu-kutsu-bōshi, chōko-chōko-uisu, tsuku-tsuku-hōshi, tsuku-tsuku-oīshi,—all onomatopoetic appellations. The sounds of its song have been imitated in different ways by various writers.

But some say that the sound is Tsukushi-koïshi. There is a legend that in old times a man of Tsukushi (the ancient name of Kyūshū) fell sick and died while far away from home, and that the ghost of him became an autumn cicada, which cries unceasingly, Tsukushi-koïshi!—Tsukushi-koïshi! (“I long for Tsukushi!—I want to see Tsukushi!”)

It is a curious fact that the earlier sémi have the harshest and simplest notes. The musical sémi do not appear until summer; and the tsuku-tsuku-bōshi, having the most complex and melodious utterance of all, is one of the latest to mature.

A lot of the poems didn’t make it into the podcast. Here are a few:

“A very large number of Japanese poems about sémi describe the noise of the creatures as an affliction. To fully sympathize with the complaints of the poets, one must have heard certain varieties of Japanese cicadæ in full midsummer chorus; but even by readers without experience of the clamor, the following verses will probably be found suggestive:—

Waré hitori

Atsui yō nari,—

Sémi no koë!

—Bunsō.

Meseems that only I,—I alone among mortals,—

Ever suffered such heat!—oh, the noise of the sémi!

Ushiro kara

Tsukamu yō nari,—

Sémi no koë.

—Jofū.

Oh, the noise of the sémi!—a pain of invisible seizure,—

Clutched in an enemy’s grasp,—caught by the hair from behind!”

Credits

Intro and outro music by Julyan Ray Matsuura