What would it mean if someone said you were turning into a tengu? In this episode I talk about Japanese sayings that are based on yokai.

Kotowaza (ことわざ) – Proverb or Saying

You know something I haven’t done in a long while? Interesting language quirks. So today how about we talk about some curious, youkai-related Japanese sayings.

Now I’ll try to explain these in a way that’s fun and easy to understand for listeners who are just at the beginning of their Japanese language studies, all the way up to more intermediate learners. And don’t worry if you know zero Japanese because they’re all so fascinating you don’t even have to know the language.

For example, if you were in a group of Japanese speakers and some told you that you were going to turn into a tengu, one of those red-faced, long-nosed mountain goblins. What would they mean? Or perhaps those same friends advise you to do your laundry while the ogre or oni has stepped out. What’s up with that? Well, we’ll cover those and a handful more.

Also, keep in mind, there are transcripts over on the Uncanny Japan website. So if you hear something and can’t rewind, or if you want to see what the kanji look like for certain phrases the whole episode will be there. Just go to the the bottom of the short blog post introducing the show under the headline in bold titled Transcript.

Hey hey, everyone, how are you doing? Officially rainy season here and so, so muggy. Humidity, frogs, and mold, that’s what we got.

Before I start, these sayings, phrases or proverbs are called kotowaza in Japanese.

Becoming a Tengu – Tengu ni Naru(天狗になる)

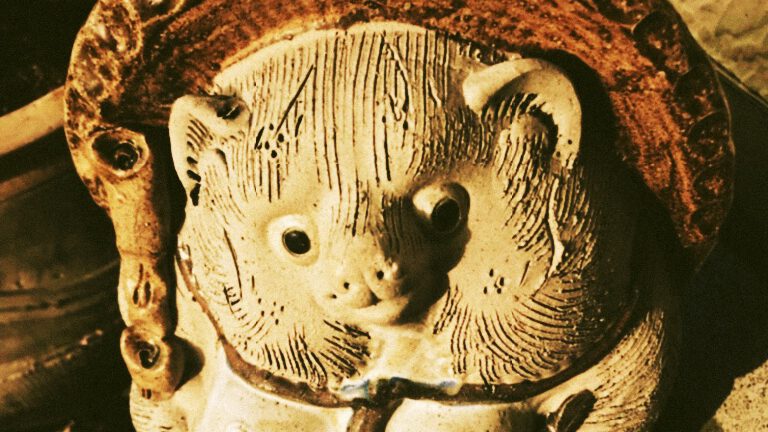

So our first kotowaza is tengu ni naru(天狗になる)turn into or become a tengu. I talked about tengu back in episode 32 and 34. If you remember them, they are those tall mountain dudes, who wear one-toothed geta shoes, ascetic Buddhist robes, sport a big ol’ pair of wings, and have crimson-colored faces with long noses.

So why would anyone talk about someone turning into a tengu? Well, first you need to remember that in Japanese to say someone is hana ga takai (鼻が高い), literally having a high nose, means that someone is arrogant, prideful, or showing off. Kind of imagine someone lifting their nose at something because they feel they’re better than that.

Okay, now visualize tengu and imagine one of them lifting or turning their nose up at something. It’s just a more powerful image. So, yeah, this is another way to say someone is a little too full of themselves or boasting.

Example. If you compliment him too much, he’ll become a tengu (tengu ni naru), so it’s best not to give him too much praise. Or perhaps you’re showing off because you just aced a Japanese kanji test and you’re going on and on about it. Your friend could say, Careful, tengu ni naru yo! Something like that.

When the Oni’s Away, Do Your Wash – Oni No Inu Ma Sentaku(鬼の居ぬ間洗濯)

Okay, let’s move on to number two. Remember we talk a lot about oni here. I hate to call them ogres or demons because those words conjure up different images for me. We know that an oni is bigger than the biggest man, brutish, rippling muscles, fangs, horns, carries a giant studded club, and wears a tiger skin loincloth. Oh, and they come in two flavors red or blue.

There are quite a few kotowaza using oni. The first one I ever heard I believe, and have heard quite a few times since is: oni no inu ma sentaku,(鬼の居ぬ間洗濯)literally, when the oni is away, do your wash. This one feels like it has two different nuances. In both cases, though, the oni is your boss, parents, teacher, spouse, or any strict, overbearing person in your life.

One meaning of oni no inu ma sentaku would be similar to: when the cats away, the mice will play. When the oni is gone, have fun! Or in this case, do your wash.

Actually, I learned that here sentaku refers to washing your emotions or feelings, not doing actual laundry. It seems the second meaning is more about being able to finally take a breather when some domineering jerk is gone for a little while.

You might also hear different variations on the phrase.

Oni no inu uchi ni sentaku (鬼のいぬうちに洗濯)

Oni no rusu ni sentaku (鬼の留守に洗濯).

Or my favorite that I’ve never heard in these parts,

Oni no rusu ni mame hiroi (鬼の留守に豆拾い). While the oni is gone, pick up beans. So there’s that.

Like and Iron Club to an Oni -(鬼に金棒)

Three. Let’s do another really common oni saying: Oni ni kanabou (鬼に金棒). This time our oni is holding or being given a large iron club, kanabou (金棒). What does it mean?

Here’s another one that is fun to imagine. Simply, if you give an oni, already this incredibly strong creature a metal club you make it even stronger, basically invincible, right? So oni ni kanabou means someone or something or some situation becoming even stronger after being given something.

It’s easier to understand in an explanation. Let’s say I was going to have a friendly competition with some friends. Something like who can make the best, I don’t know, tempura. Now, I’m pretty confident in my tempura deep frying skills. But you come along and offer to help. And you just happen to own the most popular tempura restaurant in town. Now, I felt pretty good about this competition to begin with, but if there was any doubt at all, it’s gone. Because you joined my team and there is no way we can lose. Oni ni kanabou. I could say something like, Thank you for helping out. Having you is like giving an oni an iron club. Just to reiterate, I’m the big strong oni, made even stronger by your help. You’re the metal club.

Just a side note, you and I might definitely tengu ni naru (become tengu) if we win the competition.

Even an Oni at Eighteen, Even Bancha at First Brewing – Oni Mo Juuhachi, Bancha mo Debana(鬼も十八、番茶も出花)

Moving on. Number four. We’re still dealing with oni, however, this one’s weird. The saying is: Oni mo juu hachi, bancha mo de bana (鬼も十八、番茶も出花). Let me go for the feeling on this one. The first part: Oni mo juuhachi, even an oni at 18 years of age is beautiful. The second part: bancha mo de bana, even bancha (which isn’t a very high grade of tea) is delicious on first brewing.

Basically, everything has its time. It’s important to note this is not praising someone. Best to use it in a self deprecating manner. You’d never ever use it toward someone else, unless you were being mean. Oni are these ugly vile creatures, but for a brief moment they are beautiful. Bancha is a really low grade of tea, but the first cup isn’t so bad. Again, easier to understand in context.

Example: Someone tells you, “Congratulations on your son’s engagement.” Since your son is still living at home at age 46, you could say, “Yes, he’s finally getting married. You know what they say, oni mo juuhachi, bancha mo debana.”

Being Put down in the Oni Book of the Dead – Kiseki ni Iru(鬼籍に入る)

Next, let’s move on to number five. Here’s another interesting one. And we’re still talking about oni. While I had never heard it before, all my Japanese friends had, so that’s good. It means I’m not getting to obscure here. It’s short, easy to remember and a wee bit creepy. Okay, ready?

Kiseki ni iru(鬼籍に入る)I have no confidence on my pronunciation of kiseki, but it’s not miracle, which is also kiseki(奇跡). The characters for this kiseki mean oni (a~gain!) and “register” and it refers to the King of Hell, Enma Daio’s (閻魔大王)book of souls that he carries around and writes down the name and date of every person who dies.

Now it’s interesting to note that oni as it is used here, is less what I described up above, the brutish beast brandishing a metal club, but more the ‘spirit’ or ‘soul’ of the dead. The word came from China and has those older connotations. So when you say the phrase Kiseki ni iru, going into or being written down in the kiseki, Book of Dead People, you’re in effect saying that someone has died.

An example might be something like:

A says: 最近田中さんに合わないね。Recently I don’t see much of Tanaka-san

B answers:そうよ、あのかた、鬼籍に入った. Yeah, you’re right. He’s in the Oni Book of Dead People.

I’m Sorry, Kishimoujin – Osore Iriya No Kishimoujin(恐れ入谷の鬼子母神)

And finally my favorite saying, another one that was brand new to me. As a matter of fact, it was not only new, but so odd that I asked some Japanese friends do they use it or had they heard of it before. So this one might be slightly unusual depending on who your talking to, but I think it’s worth mentioning because it involves one of my favorite demoness turned goddess.

Let’s start off with the phrase osore irimasu (恐れ入ります). This is a very polite way of saying thank you or I’m sorry. It’s one of those nuanced words like sumimasen, but more polite. You’ll hear it a lot in more formal situations. Osore irimasu.

Now my new favorite phrase is osore iri ya no kishi mojin (恐れ入谷の鬼子母神)

You hear it starts with osore iri, but the rest kind of blindsided me. I understood it but was like why? Okay, follow me here. Waaay back in episode 5 of Uncanny Japan, I talked about Kishiboujin or Kishimojin. The ogress who ate babies, then repented, then became a protector goddess of children and mothers and the insurer of safe childbirth. If you haven’t listened to that episode, it’s a riot. Anyway, that’s Kishimojin episode 5.

The phrase again: osore iri ya no kishi mojin. So why is she mentioned at the end of this phrase and what does it mean?

Meaning-wise, think of it as a fun way of saying I’m sorry, like Osore irimasu.

The phrase is a part of a silly little chant by a man named Oda Nanpo. He was a Kyouka-shi, which if you look it up in English, translates as a person who makes “mad songs”. Not quite. There more like comical poems or chants.

Now, there is a temple called Iriya Kishimojin. What Mr. Oda did was make this goofy little, nonsensical chant and in it he mushed together the osore iri and the iriya no kishimojin and thus the saying was born. Another one of my friends made a good point, she said think of it as a phrase like “See you later, alligator.” An alligator has nothing to do with anything. Anyway, it’s a bit of a tongue twister, but fun to say: osoreiri ya no kishimojin.

So that’s all for today. I had been wanting to do something language related for awhile now.

Thank you for listening and if you enjoy the show and have the means, please consider supporting us on Patreon. For only five dollars a month you can become a real live kappa and get a patron-only bedtime story, which is some Japanese folktale I’ve translated, retold, and recorded. It’s six months in and still no job, so I really appreciate and love my patrons.

Thank you.

Talk to you all in two weeks!

Credits

Intro and outro music by Julyan Ray Matsuura

Summer Ambient Piano by Rafael Krux

Link: https://filmmusic.io/song/5504-summer-ambient-piano-

License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Medicine by WinnieTheMoog

Link: https://filmmusic.io/song/6256-medicine

License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/